Some of the looted Buddha heads that have found their way to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Image courtesy of the author

Decapitated Buddhas At Borobudur

By V. R. Sasson | 2018-01-17

I knew to expect them. But it’s one thing to know something theoretically, and something else entirely to experience it for oneself.

My seven-year-old son and I made it to Borobudur just before sunset. We walked toward the ancient Javanese Buddhist complex in silent awe. The stupa rose before us like a haunted memory, unearthed from a mound of volcanic ash after centuries of isolation. It was more beautiful than I ever could have anticipated.

We circumambulated the site one layer at a time, marveling at the craftmanship. We kept reciting the details we had learned: that it was constructed out of more than a million blocks of stone. That each one had been pulled from the rubble, restored, and returned to its original position, so that the entire monument had been built all over again.

The structure guided us on its walkway into the sky. We read as many images as we could interpret, following the story of the Buddha’s life. Beautiful carvings met us at every turn—Jataka scenes, the story of the Buddha’s birth as Maya reached for a branch, the scene of the archery competition with Yasodhara as the prize, nagas raising their mysterious heads. From one level to the next, we marveled at the countless secrets this extraordinary monument had to offer, wondering at the symbolism it was seeking to express. When we reached the top, the sun was slipping from the jungle sky, flocks of birds were taking flight, and Muslim calls to prayer could be heard coming out of the villages all around. The privilege of that moment—of standing on Borobudur with my son—was a dream.

Decapitated Buddha statues at Borobudur. Images courtesy of the author

But dreams can be just as complicated as reality, and this one was no less so. Borobudur is also the haunt of decapitated Buddhas—the remnants of a looted past. In between magical moments, I took the time to point out these statues to my son—headless bodies seated in meditative repose, hands resting serenely on their laps; the very embodiment of silent contemplation. And almost every single one a victim of methodical beheading.

A few months later, I was in New York visiting family. My husband and I had reserved a day for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As anyone who has been knows, there’s nothing quite like the Met. It is in many ways the best part of New York City—the very reason New York is such a special place. Where else in the world can such a magnificent collection be found? Each time I visit, I am humbled by the scope of learning it represents. It provides an encyclopedic education of human achievement, and like all great encyclopedias, one lifetime is simply not enough to explore its vast depths.

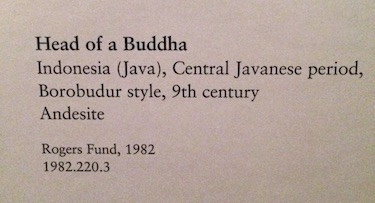

But this trip was different. I was not prepared to encounter what I found hanging on the wall, but there it was: a Buddha head from Borobudur. Decapitated plunder, missing its body, framed in an open box. I recoiled instinctively, as though I had encountered a corpse.

A Buddha head stolen from Borobudur, now on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Image courtesy of the author

What alarmed me most was the fact that there seemed to be no shame in its exposure. The curators of the Met apparently thought nothing of it. They were proud to hang a Buddha head on a wall, as though it was the most natural thing in the world. As though there was no headless body left behind. On the description beside it, the curators explained that it was from Borobudur. They knew what they were doing, but it was just another object to them. They did not explain its provenance or anything about how the head had found its way there. They did not remark on the fact that it had once had a body to go along with it. Nor, indeed, did they seem to mind all the other Buddha heads lining the wall next to it: one Buddha head after another was proudly displayed, as though the exhibits made perfect sense. As though none of these images meant anything more than encyclopedic information about human achievement and craftmanship. It was art. It was information. It was just a head.

I imagine non-Buddhist readers might find my reaction bizarre. It is, after all, a piece of art. But in the Buddhist world, it is more than mere art. Some Buddhas can, of course, be art, but not the ones consecrated on stupas and other sacred sites. Those Buddhas are in many ways living beings, devotional expressions that speak of much more than human artistry. They reflect a community’s hopes and aspirations. They are prayers embodied. They are part of a living tradition and not some long-lost curiosity.

Even in the Met, visitors leave devotional gifts before a statue of the Hindu deity Ganesh. Image courtesy of the author